Flying the Land that Time Forgot

From 1972 to 1980 Kent Bergsma had the unique opportunity to live and fly small aircraft in what many consider the most primitive place on Earth. During those years. Irian Jaya, Indonesia (eastern half of the Island of New Guinea now called Papua) was still considered "stone age." In fact, Kent was involved in making contact with some tribes who had never seen a white man nor made any contact with the outside world. How could this still be true in the late 20th century? Maybe that is why this mysterious and isolated land has often been referred to as the "land that time forgot."

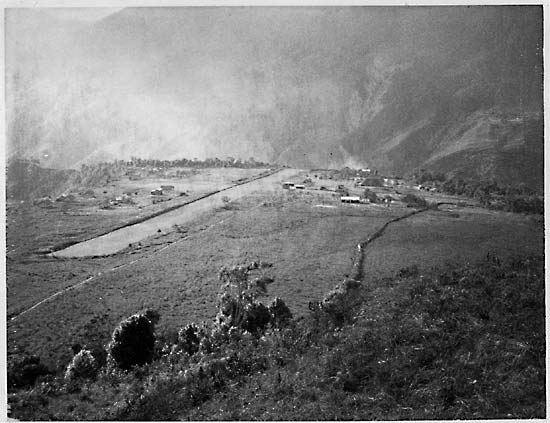

Since there were no roads into the highland ranges (with mountains toping 16,000 feet), everyone and everything had to be flown into the interior by aircraft. Short undulating and sloping dirt airstrips were scattered throughout the highlands at elevations ranging from 4000 to 9000 feet. Not only flying but just living day to day in this environment was a huge challenge.

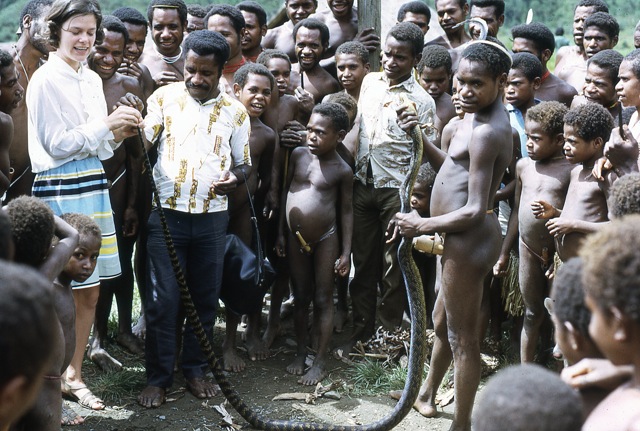

The picture below was taken in 1973. In the background you can see the types of sloping airstrips and short angling approaches he had to fly into. And dangerous airstrips were not the only thing he had to deal with. It was not an easy life.

Kent and Linda Bergsma in the highlands of New Guinea (Papua).

Kent and Linda Bergsma in the highlands of New Guinea (Papua).

Here is what Kent has to say about his experiences:

"First, I must pay a special tribute to my wife (of 41 years), Linda, who enthusiastically followed me half way around the world to live in some of the most primitive conditions imaginable. No TV, no radio, no stores, no car, no electric appliances and sometimes no fellow ex-patriots to socialize with. She helped bandage the wounded, nourish the hungry, teach the children and always was there to help me complete my flights and get home safely. Our first child, Kaia, was born in a primitive hut on the jungle south coast. She even tolerated snakes in the pantry.... :-) And, in the eight years we lived and worked there, she never once complained.

Since we left Indonesia, we often find ourselves recounting our experiences to family, friends and acquaintances. The response to our stories is almost always the same. “Hey, I hope you are writing a book about this.” I laugh and say, “I am working on it and hope to finish it someday.” Many have encouraged me to get it finished! And recently the question has come up about the possibility of doing a series of video documentaries. I do have a number of super 8 sound movie clips along with hundreds of pictures I took when we lived there. So with the prodding of my children, I have begun writing the script for a new video."

A video is in the works:

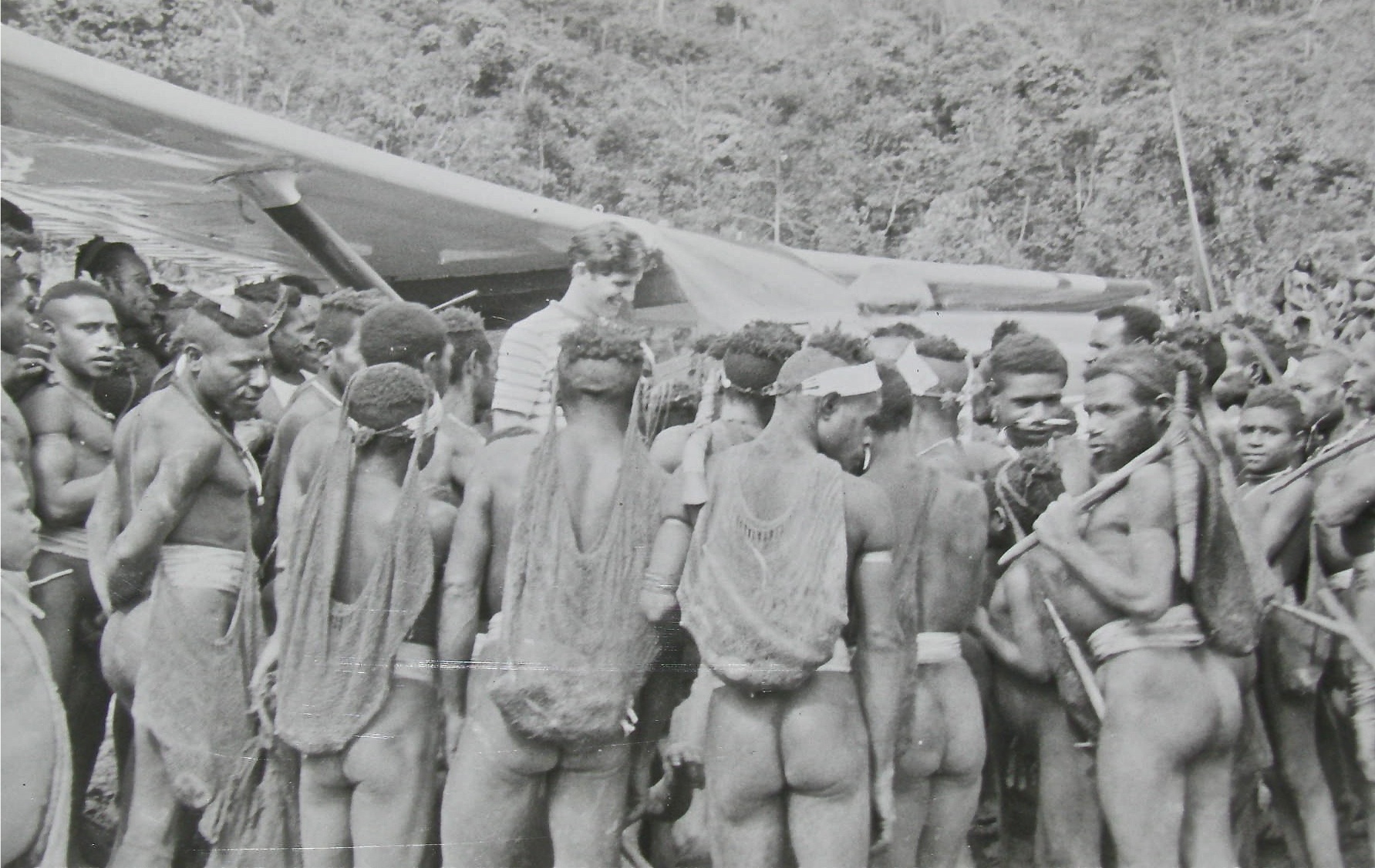

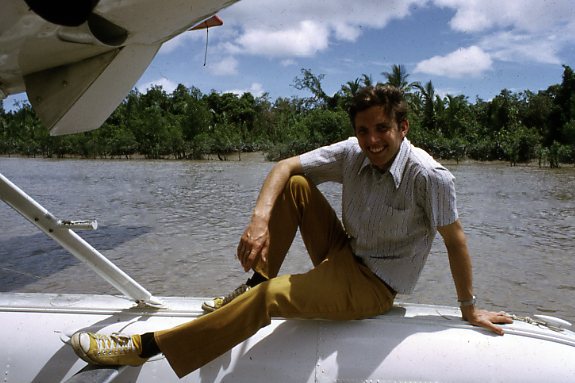

The title of my first video is "First Contact" and it will recount this story: In the early 1970's I had the privilege of making the very first landing into an isolated village in the Eastern Highlands. They had only seen one white man before and never a plane close up or a pilot. Imagine what they thought when they saw the plane land, followed by a tall pale skinned being stepping out of his big red and white bird. The story is both amusing and quite eye opening. In the picture below you can see me being surrounded by all the tribe's warriors shortly after I landed. Was I scared? You will just have to wait to see the video (due summer 2011) to find out.

A book is in the works:

Someday Kent hopes to finish the book he is writing about his experiences. The title will be:

FLYING THE LAND THAT TIME FORGOT

"A bush pilot’s tales of survival in a distant stone age land"

He will share with you a "day in the life of a New Guinea Bush Pilot. It always began with a very thorough pre-flight inspection. That included dipping the fuel tanks with a marked dipstick to check total fuel on board. Now you know why Kent is reluctant to trust engine instruments.. :-)

Here are some excerpts from one of the chapters titled "Nine Lives."

Chapter 9: Nine Lives

INTRODUCTION: People often ask me if I still fly airplanes. Recently, when we were eating out with our grown children and a few friends this question was asked again. My youngest son promptly replied. "I know why. Dad, you are like a cat with nine lives. The only problem is you have used them all up." I was surprised by his answer. It was a very astute reply for a young man. As I later thought about what he said, it gave me the idea for the title to this chapter.

That evening I sat down at the computer and began outlining the really "close calls" I had during my bush flying career. To my amazement, I confirmed there were nine of them. In every one, the margin between life and death was very, very small. Was the fact there were nine just a coincidence or a serious warning? Read on and you I will let you be the judge.

Typical mountain landing strip

Typical mountain landing strip

Incident No. 1: Blown engine at 9,000 feet

This is the story of my first harrowing flight incident in the highlands of Irian Jaya, Indonesia. It happened when Linda and I had only been in the country for four months and I had only a few weeks of experience flying the dangerous mountain terrain. This particular incident taught me a very valuable lesson that served me well for the next eight years. At the time this happened we were living at Bokondini, a small village with an airstrip on a 4000 foot plateau in the central highlands. This outpost was approximately 150 miles south and west of our main base, Sentani, which was located on the central northern coast of the Island. Sentani, formerly known as Hollandia, was the hub of our flight operations in Irian Jaya. All cargo, supplies and inbound passengers first came through Sentani to make connecting flights into one of the many interior airstrips. Since there were no roads into the central highlands, everything and everyone had to be transported by aircraft. At least two to three times a week I would fly my Cessna out to Sentani to pick up passengers, cargo and supplies and fly them back into the interior.

A normal flight was approximately an hour and 10 minutes one way and took me over some of the most dense and unpopulated jungle on the face of the earth. No pilot wanted to think too much about loosing an engine over those jungle swamps. They were full of poisonous snakes and crocodiles, and there were miles and miles of dense tree canopy that was over 200 feet above the ground. On numerous trips I can remember looking down and trying to decide, Ok, if I loose an engine, am I going to land in the trees and risk a 200 foot drop through the canopy to the jungle floor, or would I be better off landing in one of the winding rivers and battling it out with the snakes and crocodiles? Either option was not very pleasant to think about. In fact, I just stopped thinking about it and did my job flying the airplane.

Weather was a constant problem on all our flight routes. The weather in Irian could be very unpredictable and unforgiving. Changes occurred quite rapidly and without warning. We had no flight service centers, no weather forecasters and no doppler radar! All we had was a good eye, a chart, compass, and the seat of our pants! But I could always accurately predict one thing. The later in the day, the greater the possibility of running into bad weather. Like most tropical countries with mountainous terrain, the weather patterns in Irian Jaya follow a set pattern. Early mornings usually start out with blue sky and some fog hanging around in the valleys from the previous night’s rain. By 8 am, the fog begins to burn off and you will experience beautiful calm weather. By 10 am, wind in the valleys start to pick up from heat rising up the mountain slopes. Wisps of clouds begin to form along the ridges of the mountain tops. By noon, the clouds would start building rapidly and begin affecting my flight paths. By 2 p.m., the entire region can become grey and ominous with light rain falling in many areas. By 4 p.m., the sky regularly opens up and the highlands close down with severe rains and thunderstorms that continue into the late evening hours. The next morning it will be clear and the cycle repeated all over again. When it did rain, it really rained. This pattern produced over 200 inches of rainfall a year! This highland weather always affected my flight planning and determined most of my daily scheduling. My goal was always to complete my flights and to be back on the ground at our home base by 3 in the afternoon.

One day I was running a little behind schedule when I landed at Sentani to pick up another load to fly to the interior. It was past 2 p.m., so I decided to quickly get the airplane loaded and hope for the best. As I looked off towards the mountains, I could see the weather was starting to build rapidly. I knew if I did not get airborne quickly, there would be a good chance I would not be able to make it home. If the weather closed down in-route, I would have no choice but to turn around and come back to Sentani for the night. I loaded the plane with haste, jumped in, and started cranking the engine. As the engine turned over, I heard a noise that did not sound quite right. It was very faint and sounded a little like an exhaust leak. The engine fired right up and idled smoothly. I sat there for a few seconds and analyzed my engine instruments. Everything looked and felt normal. Could that strange sound just have been my imagination? Since the engine seemed to be running fine, I decided to take off and hightail it for home. What I did in those few seconds was to fall prey to a disease that we pilots call “Get-home-itus”. Even though my gut was telling me something wasn’t quite right, the strong urge to get home overpowered my better judgement. I rationalized away my concern by telling myself, “Oh, everything is going to be o.k., it is just a minor problem I can look into later.” Add to that I was in a hurry to beat the weather, and I was setting up a formula for disaster. Unfortunately, this same scenario, which I had been warned about, has killed many a pilot over the years. But it did not stop me this time. I called the tower, taxied to the end of the airstrip, applied power, did a straight out departure and headed for the mountains. The only thing on my mind at that point was to try to beat the weather and get home. Ten minutes after takeoff, I called Bokindini to notify them I had departed Sentani, was in-route and my ETA (estimated time of arrival) would be approximately one hour. I climbed up dodging a few thunderstorms, and leveled off at 9,000 feet. It was a bit of a bumpy ride, and I could see up ahead that I was just going to have to skirt around a few thunder storms. The interior reported light rain was beginning to fall, but the valleys were still open.

Fifty minutes after departure, I cleared the lowland jungles and started up the long, narrow valley leading towards our highland base. I was maintaining my altitude at 9,000, the weather up ahead appeared to be holding and everything seemed just fine. On the flight inbound I had been monitoring my engine instruments. The cylinder head temperatures, oil pressure, oil temperature and fuel flow were all functioning within normal limits. I was just getting ready to pick up the microphone to give a position report when all of a sudden all hell broke loose in the engine compartment. There was a loud explosion followed by a terrible banging noise. It quickly became obvious to me that something was repeatedly hitting the cowling of the engine. I quickly looked down at my engine instruments to try to pick up any clues on what was happening while pulling the power back to reduce the noise. I couldn’t determine what had happened, but I knew it had to be ugly. I was going to have to land whether I wanted to or not. I was 20 minutes out of Bokindini and knew there was no way I could get home on reduced power. Then it struck me. I remembered on previous training flights that there was a remote abandoned airstrip somewhere in the valley I was flying over. I quickly looked around to the left and right side and up ahead straining to locate the airstrip. Finally, I rolled the plane up into a steep bank and directly underneath me was the abandoned strip, Kobakma! I could not believe my good fortune or maybe it was something more than luck. I decided to keep the engine running for a while longer even though It was still banging and clanging, all the while keeping a close eye on the oil pressure and fuel flow gauges. I knew I should get on the ground as soon as possible and started a spiraling descent right over the airstrip. Within a few seconds of starting the descent I began to smell gasoline fumes. That is when I became very concerned, in fact, down right scared! For a seasoned pilot here is nothing worse than the fear of in-flight fire. Planes can glide just fine without engine power, but they don’t fly long when they are on fire! I reached for the microphone, clicked the button, and was just starting to say, May-day, may-day!, when I stopped. “I thought, No, I cant do that.” I knew my wife, Linda, might standing by the radio at Bokindini and if I came on with a frantic may-day, that it would freak her out as well as everyone else listening on the open radio channel. So instead, I casually said, “Bokindini, Bokindini, this is Mike-Charlie-Kilo. I am experiencing engine mechanical problems and will be landing at Kobakma in a few minutes. I will report in once on the ground. Out.” I immediately turned the radio off because I did not want to be distracted by incoming radio traffic. I pulled the power all the way back, slowed the plane down, pulled on 20 degrees of flaps, and put the plane into a steep banking spiral to increase my rate of descent without building up excess airspeed.

Landing Kobakma without an engine

Landing Kobakma without an engine

I was becoming increasingly concerned with the strong smell of gasoline that was entering the cockpit. I knew I had to shut the fuel off, but wanted to be sure I could make it to the strip. With the engine shut off there would be no room for any error in the approach. So I kept the spiral tight and directly above the airstrip to prevent any chance of overshooting the runway and landing in the jungle. When I was sure I had the field made, I reached over, pulled the mixture and turned the fuel selector valve to the off position. This immediately stopped fuel flow and shut the engine off. I banked onto final approach at 85 mph and made a fast, steep descent to the end of the airstrip. I only pulled on full flaps on very short final approach when I was sure I had made the strip. I tagged the Cessna 185 right on the end of the airstrip and immediately applied heavy braking as it rolled quickly up the sloping strip. As the plane responded to the braking and slowed down I I began to relax and breathe again! Using the last bit of momentum at the top of the airstrip, I spun the plane around 180 degrees and stopped. I remember it was so quiet in the cockpit. I just sat there for a moment trying to catch my breath and mentally grasp what had just happened.

The whole incident transpired very quickly. When it was happening, it seemed like it went on forever, but from the time the engine blew to the time that I was on the ground less than 5 minutes had passed. I remember sitting there a little dazed and thinking to myself, “Boy, that was exciting.” I did not realize just how dangerous the whole situation was until I opened the door and stepped outside the airplane. I turned around and I could not believe what I saw. The entire belly, sides, and tail of the airplane were covered with engine oil. It looked as if somebody had tried to paint the plane with a big brush and a bucket of old used engine oil!

Very quickly the local natives started to surround the airplane. From all the commotion, I figured they knew something was wrong, I know they had not seen an airplane with this kind of gooey substance all over it before. They were chanting and clicking their gourds with excitement. I decided that I had better call in before people started worrying about me. I think the whole island was holding their breath because I had suddenly gone off the radio for those few silent minutes. I quickly turned the key back on, fired up the radio and called Bokondini and said, “This is Mike-Charlie-Kilo, calling in to report I am safely on the ground at Kobakma with a dead engine. I will be doing an inspection of the damage and will get back to you soon.” I looked at my watch and realized it was after 4 p.m.. It was getting late enough in the day that I knew nobody was going to be able to come and get me. I knew I was looking at an overnight stay in the middle of the jungle.

I pulled my trusty tool kit out from under my seat, grabbed the screwdriver and decided I should probably go ahead and open up the top cowling section of the engine. I was dying to see what had actually happened by surveying the damage inside the engine compartment. When I loosened up the screws and lifted the cowling off, I quickly realized just how fortunate I was. I was standing there staring with amazement at a damaged cylinder head. The head had separated completely from the cylinder barrel! The failure was so violent that it had torn the fuel injector line loose and cracked open the exhaust manifold. The engine had been spraying raw fuel all over the hot cylinder head and opened exhaust. It took a few moments for all of this to sink in, but when it did, I realized that the outcome of this incident could have easily been fatal. Not only was it a miracle that the engine did not catch on fire, it was a miracle that it happened right over the top of an airstrip. If this would have happened five minutes earlier or later, I would have not made it to the airstrip. Another 10 minutes earlier I would have been going into the jungle swamp with all those crocodiles and snakes I told you about. 10 minutes later I would have had to put the plane down in high mountain terrain. Not only had the cylinder head severed from the barrel, but the engine had pumped out almost seven quarts of oil out of the engine’s total of eight quarts! So, no way was I going to be staying in the air any longer than a few more minutes. I fired up the radio again and called the main base and explained the situation and my thoughts on getting me and the plane safely out of there. I figured I could repair the engine onsite if someone could arrange to fly in the needed parts. I was going to need a complete new cylinder assembly, exhaust manifold assembly, fuel injection lines, wires, gaskets, etc.

Spending the night in the local village

Spending the night in the local village

Since I was going to have to spend the night in the native village, I prepared myself by grabbing my mosquito net and other survival equipment out of the back of the airplane. I buttoned up the aircraft and headed off with the chief to their village high above the airstrip. I could not speak the local dialect, but it was obvious they were excited to have such a special visitor. They killed their best chicken and prepared a small feast in my honor. After dinner I retired to a small round hut provided by my hosts. It was a good thing I carried that mosquito net in my plane as the pesky insects filled the hut. It was a very restless evening. Not only did I have to sleep on a hard bark floor with no mattress, but as I lay there, I found it hard to get to sleep as I thought about the events of the day. This incident could have had a number of different endings which all would have been disastrous. I thought long and hard about what I should learn from it and how I could avoid a repeat in the future. I knew the airplane was trying to “talk to me” back there on the ramp when I cranked it up. I didn’t listen. The moral of the story was - if you hear a strange noise and something doesn’t seem right, then check it out before taking off. Do not ignore it. I also determined to never fall prey to get-home-itus again. I even instigated a more aggressive engine inspection program. The lessons I learned on that fateful day served me well and played a key role in keeping me alive.

During the remainder of my flying experience, there were a few other times when I knew things were not quite right and I stopped and I made sure they were right before I took off. Like with many mistakes or accidents in life, airplane crashes are usually a result of a multiple chain of events or decisions that are progressively linked to each other. Airplanes can be very unforgiving. If you are going to fly in bush conditions you must understand this principle to be a safe pilot. You must be vigilant at all times. When you sense something is not right you must break the chain or risk getting killed. With this incident the chain could have been broken if I would have said to myself, back in Sentani, “Ok, this doesn’t sound right. I need to shut this engine down and get out, open up the engine and see what is going on.” Upon a close engine inspection immediately following this incident, I found severe exhaust and oil staining around the cylinder barrel. This indicated a small compression leak between the cylinder head and the barrel that had been going on for some time. I would have seen this if I would have taken the cowling off and looked things over. The evidence would have shown me something was not right with number 2 cylinder and all I would have needed to determine this were my eyes!

Because of this experience, I made a decision to start a new inspection procedure that was not required or even recommended by the FAA. I called it my 25 hour visual engine inspection and used it successfully for the rest of my flying career. With commercial aircraft, we were required to perform a complete airframe and engine inspection every 100 hours the plane flies. This requires opening up key inspection covers on the airframe and removing the engine cowling to facilitate a visual check list of key aircraft systems and components. Doing this helps spot potential problems. I discovered a lot can happen to the engine in 100 hours. My last inspection did not pick up the cylinder head problem. The looseness of the cylinder head and the consequent failure probably happened in 20 hours of flying, not 100. I immediately started a procedure where every 25 hours of flight time I would remove both halves of the cowling and give the engine a thorough visual inspection. This only took me 30 minutes, but I recall there were at least another 8 to 12 instances when this inspection helped me spot little problems that, if not attended to, could have developed into a severe problem or even potential engine failure.

What happened on that day never happened to me again. Other things did happen as you will learn in the following pages, but I did not have another incident that was related to ignoring strange airplane noises (plane speak) or get-home-itus. This may be a good case for believing there is a reason for everything that happens in your life. The important thing is, we can all learn from these lessons to prevent the type of problems that can lead to disaster.

Note: The following are introductions to the other 8 incidents

Incident No. 2: Lost Over the Jungle and Running Out of Fuel

As a bush pilot you are often pressured by your passengers to do things you know you shouldn't. To keep your “customers” happy it is sometimes easier to just bend to the pressure. My inexperience and lack of good judgment could literally have been the death of me. As with the first incident, the lessons I learned were also burned deep into my consciousness and helped keep me alive in the years that followed. I learned a good hard lesson about saying no and a huge lesson about fuel management. There is an old saying among bush pilots, The only time you have too much fuel on board is when the plane is on fire. I think after you read this story, you will see why I became a firm believer in this adage. Before I get started in the details of the incident, let me share with you a little background.

As a pilot in training you are taught early on how to properly manage your aircrafts fuel supply. When you are in the air you just aren’t able to pull off to the side of the road on short notice, pick a service station and fill it up. Flying an airplane requires you to plan not only for the amount of fuel you will need for your flight but also for the potential of the unexpected. You never just carry enough fuel to get to your destination and back. Any pilot will tell you that it is the unexpected that can get you in trouble, and running out of fuel can be very embarrassing and sometimes fatal. As a bush pilot I was taught to always carry an extra hour of flying time in the fuel tanks. That may seem like a lot of extra time, but when you are flying over isolated jungle with no roads or airstrips to land on is 1 hour really enough?? After I share this story you will know why I changed my fuel management philosophy.

To be continued ...

Incident No. 3: Out of Airspeed and Out of Runway

When an airplane’s wing loses lift it stalls. To recover from a stall you need to lower the nose and apply power to get the airplane flying again. This is not such a big deal unless you are close to the ground when the stall occurs. If that happens, you can only hope you have enough altitude that allows you to lower the nose and regain lift and control before you hit the ground. If the stall is not corrected early enough the airplane can go into a spin which requires even more altitude to recover from. Even a skilled pilot cannot recover from a stall/spin event if it occurs too close to Mother Earth. Stall/spin accidents are almost always fatal.

From very early in his training a pilot practices recovering from stalls. For safety, practice is done at high altitude. Not only is it important to know how to quickly recover from a stall, it is even more important to know the signs of an impending stall. It is much better to avoid the stall altogether than have to fight the plane trying to recover from a full stall. In my training we practiced stalls from all types of attitudes including dives and steep banking turns. Each airplane will give its own type of warning that a stall is close. Some planes will shudder while others will give you a distinct “loose feel” in the control surfaces. I practiced stalls until I was blue in the face!

I never realized the true value of this training until I was coming in to land late one afternoon at home base. Five minutes out Linda reported heavy gusting winds. As I made my way up the valley I could tell by the leaves on the banana trees that the wind was blowing directly across the runway at 20 to 30 mph. I looked over at my friend who was riding in the right front seat and made the comment, “This could be interesting.” Little did I know just how interesting and exciting this landing was going to be, and little did my friend know how close we came to “buying the farm.”

To be continued ...

Incident No. 4: Trapped in Bad Weather and No Where to Go

This is one story I do not like to tell. It is not suppose to happen to good pilots. But, it has happened to a great number of very experienced pilots. If you are a pilot you know what I am talking about. You have heard the stories and read the news of the latest incident where a pilot has been lost in bad weather and rough terrain. For pilots, tall mountains and bad weather are not a good mix. If you don’t have a great respect for them they can become your worst nightmare.

If you are flying near mountains and suddenly find yourself surrounded or trapped by rain and clouds you don’t just fly through the clouds hoping your instruments will safely guide you through. This was even truer then than it is now. Where I flew in the 1970’s there were no radio stations to home in on, no navigational aids and certainly no GPS available. Attempting to fly in these conditions could be deadly, as you never know which clouds ahead have mountains hidden inside. Pilots often refer to these type of clouds as "cumuli-granite clouds." This bad mix has probably been the number one cause of experienced pilot deaths in bush type flying around the world.

This danger was drilled into me early on in my flight training. Just before arriving in Irian Jaya an MAF pilot was killed when he was trapped in a blind canyon in bad weather. This was a tragic accident and it reinforced my commitment to weather safety. I was determined it would never happen to me. How wrong I was!

To be continued ...

Incident No. 5: Above the Weather at 18,000 Feet and Out of Oxygen

People are often surprised when I explain I had to fly over mountain ranges topping 16,000 feet. An expansive and rugged mountain range ran east and west through the interior of New Guinea. It is one of the reasons the indigenous people were hidden from the outside world until World War II. It is also the reason we had to use airplanes to travel at all. It was also the core of the weather factory in Irian Jaya.

The Cessna 206 I flew had a turbo charged engine that would allow me to climb with a load on board up to and over this tall range of mountains. I also had to carry an oxygen bottle on board to make these flights. For safety I would usually put on my oxygen mask any time I climbed over 12,000 feet for any extended period of time.

It was a beautiful calm morning when I took off from out central mountain base to head over the mountains to the south coast. I was to land at the mining company airstrip at sea level and pick up a full load of supplies to bring back. My flight route took me right over Mt. XXX. At 16,500 feet it was a beautiful sight as I passed over and looked down at the snow covered glacier peak. It was 10 am. The sky was clear and I could see for a hundred miles.

I landed at 10:35 a.m and casually began loading the plane. It was very hot and humid and I was not particularly inclined to hurry. Why should I sweat? The weather was beautiful. I took off at 11:05 a.m. and climbed out north towards the mountains. Since I had a full load on board and had to climb to 16,500 feet I knew it was going to take a while. As I was climbing out I realized that clouds had begun to form along the tops of the mountains. In less that a half hour clouds had started to build in the upper valleys as well and I found myself on a race to out climb them. Clouds were building up as fast as my plane was climbing. No worry I thought. I have oxygen on board if I have to go higher to get home.

To be continued ...

Incident No. 6: Heavy Rain Takeoff and Plane Won’t Fly

Planes fly through air. They don’t fly too well through water. Lift is created by a pressure differential as air passes over and under the wing. I had taken off many times before in rain. But seeing how there was always more air than water I never had a problem. Not until the day I took off with a heavily loaded Cessna 185 in a heavy (and I do mean HEAVY) tropical downpour. This was a real nail bitter and taught me another valuable lesson that I am very happy to be alive to tell about.

To be continued ...

Incident No. 7: Fog Trap on Downhill Landing

Airplanes are normally landed into the wind. On mountain airstrips they normally land going uphill. In both cases the goal is to land with minimal speed over the ground and use the wind or slope to help slow the plane down. It is possible to land an airplane going with the wind or going downhill. This requires more pilot skill and can be a little risky depending on the runway length, amount of wind or the runway’s degree of slope.

When flying in the bush, a pilot is not always presented with ideal conditions and sometimes he must consider the option to land against the norm. Experience and training lets you know how far to push it. When I was faced with such a decision, I would circle the airstrip at least two times and review in my mind all the variables. Direction and strength of the wind, downdrafts and gusts on short final, roughness of the airstrip, slope and undulations of the surface, approach obstacles and overrun area, total weight on board, and temperature and humidity - these would all be run through my mind before I made the final decision to land or abort.

Early one morning I was inbound to pick up a load of passengers at a central highlands airstrip. The strip was situated in the center of a small valley and was 7600 feet above sea level. One had minimal maneuvering room and both the approach and departure paths required some tight turns. As I flew into the valley I noticed a bank of fog sitting out off the normal approach end of the runway. Circling overhead I was able to determine there was not enough room to maneuver in for a normal landing. I began to consider attempting a down hill landing. Since the airplane was empty and the slope no more than 4 percent I felt I could do it safely. I knew I had to be certain I could pull it off as the fog sitting off the other end who prevent me from making a safe go-around if I should fail. Everything had to be just right. I went over the conditions again it my mind as I circled one more time. The decision was a go. I lined up on final approach, pulled on full flaps and slowed the airplane to a crawl. I was going to plant the airplane right on the upper end of the runway.

Little did I realize the danger ahead. There was one thing I did not consider and it almost cost me my life!

To be continued ...

Incident No. 8: Engine Quits on Final Approach over River Gorge.

Since my first engine failure in 1972 I had not had any further engine problems. Through diligent inspections and maintenance I believe I was able to avert engine trouble. Once an engine failure does happen, you will fly with it always in the back of your mind. You may find it increases your awareness of where to set down in an emergency landing - always keeping an eye out. It may mean you become much more sensitive to engine sounds - always keeping an ear out. But no matter how hard you may try to prevent it - stuff does happen - especially mechanical stuff!

It was the spring of 1979 and we were nearing the end of our term of service. We were scheduled to be back in the U.S. by the end of the year. I had been asked to stop by our flight operations in Kalimantan, Indonesia on our way home to help out on some construction projects. We had begun packing up our belongings. I still had a couple weeks of flight schedules to work through in Irian Jaya before leaving. Little did I know it was going to happen all over again. Only this time I happened along a rugged river gorge and I heard no strange sounds, no warning and only seconds to act.

To be continued...

Incident No. 9: Racing against Weather and Darkness

This final incident occurred just before we were scheduled to return to the States. It happened on Halloween day 1979 and was the last flight I made in Indonesia. I was in Kalimantan (formerly Borneo) to oversee the construction of three aircraft hangars. The hectic building schedule didn’t allow for anything else, so I was taken off active flight status. But one day the program manager asked if I would make a short flight east of Pontianak to pick up an Australian road-building crew. He was under staffed and assured me It was an easy flight - 30 minutes out and 30 minutes back in clear weather. He confirmed the Cessna 185 was already fueled with 2 hours of flying time and ready to go.

When I got to the airport I decided I just wasn’t comfortable with the amount of fuel on board. My inner voice was prodding me to add fuel but I looked at the clear weather overhead and tried to convince myself that maybe I was being too cautious. My mind quickly flashed back to incident No. 2. Remember the commitment I had made? That commitment won the debate. I was even a little embarrassed when I asked the ground crew to help me put another 20 gallons of fuel on board.

I warmed up the engine, went through my departure checklist and accelerated down the runway for a straight out departure to the east. As I was climbing out I looked behind me. What I saw sent chills down my spine.

Wait until you hear what happened on this flight - on Halloween no less...

CONCLUSION: Maybe it was time ... (to be continued)